Although I don't follow the model portfolios exactly, I am a big fan of the principles of the Canadian Couch Potato. It has demonstrated the virtue of staying invested in a diversified, low cost, small and easily understood set of broad index funds. It is called couch potato since you rebalance about every year, but otherwise just leave it alone. The simple couch potato portfolio has had solid performance and limited volatility over the long run, bettering many mutual funds, all with very low fees.

Although I don't follow the model portfolios exactly, I am a big fan of the principles of the Canadian Couch Potato. It has demonstrated the virtue of staying invested in a diversified, low cost, small and easily understood set of broad index funds. It is called couch potato since you rebalance about every year, but otherwise just leave it alone. The simple couch potato portfolio has had solid performance and limited volatility over the long run, bettering many mutual funds, all with very low fees.I suspect most readers are already very familiar with the Canadian Couch Potato but in case you are not, I urge you to regularly consult their website, and to give full consideration to their model portfolios. Recently they have also started a podcast series that I also recommend.

The folks at Canadian Couch Potato have model balanced index portfolios for conservative to aggressive investors. They show how to implement them using ETFs, Tangerine investment funds, or TD e-series products. Interestingly, the long term performance only varies slightly across the different risk portfolios, but that is a topic for another post.

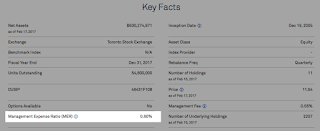

The other day I was examining their ETF based model portfolio (see screen capture below), and I was struck that the values they gave for weighted MER for each portfolio seemed too low to me.

|

| Screen capture (Feb 2017) of the Couch Potato model ETF portfolios. Note the weighted MER line. |

Just to be certain, I first checked with both morningstar.ca and with BMO directly, and sure enough both currently (late Feb 2017) give 0.23% as the MER for ZAG. I proceeded to calculate the weighted MER for some of the portfolios using that value, and for the conservative model portfolio it was 0.209%, versus the Couch Potato value (see screen shot above) of 0.12%, while for their balanced portfolio, with 40% Zag, 20% VCN and 40% XAW, I calculated a weighted MER of 0.188 versus the stated value of 0.14.

I could see from the weighted MER values in the model portfolios that the difference must be in ZAG, since the differences were higher for the portfolios more highly weighted in that, so I dug around a bit more. The ZAG MER value that they used in their calculations was 0.10%, not 0.23%, I was able to determine by backward engineering from the weighted MER. If I assume that value for the ZAG MER, I obtained 0.118 for the conservative portfolio and 0.136 for the balanced one, both consistent with the weighted MER given on the Canadian Couch Potato site. So you ask, which is the correct value for the ZAG MER, 0.23% or 0.10%?

The stated MER for funds is normally obtained from audited financial statements. Of necessity that is based on results from the recent past, since the auditors only get to work after the financial documents for the financial year have been completed. In the BMO ZAG case an asterisk notes that the MER is based on the 2015 year audited statements.

Since that time, BMO have announced lowering of management fees on a number of their ETFs, including this one. For ZAG, they lowered the management fee to 0.09, and they estimate that that will result in a current MER of about 0.10. Problem solved.

There are several implications for investors, however. The true MER is based on audited financial documents. Since management fee is the dominant component of most ETF MERs, if that is announced as lowered, we can expect the MER will drop by a similar amount. For most ETFs the MER is pretty stable from year to year. If the MER has dropped significantly, we need to evaluate whether we are confident that it will stay at this lower value, and if the return of the fund will change due to the different amount of investment advice, supposedly related to the management expense.

Secondly, when making long term ETF choices and comparing similar products, it is important to go beyond the stated MER, to make sure that there are not significant recent changes that will influence the current and future effective MER. For example, with the previous MER for ZAG, it appears obvious that the similar bond ETFs VAB from Vanguard Canada and XQB from iShares have lower MER values. That situation is reversed, however, with the lowered management fees for ZAG.

While the MER is to be based on audited statements, the management fee can be adjusted to the current value. An easy way to check if there has been a significant change is to examine both the MER and management fee for the fund you want. Normally the management fee makes up most of the MER. If they are very different, check around for announcements of recent management fee changes, and in particular check company statements about whether the lowered fees are temporary or a long term change.

Some readers will correctly point out that the difference here is small enough that it may well be lost in your overall financial fees. If you had invested $10,000 in ZAG the difference per year in the two MER values would be $13.

This posting is intended for education only and should not be considered investment advice. The reader is responsible for their own financial decisions. The writer is not a financial planner or investment advisor, and reading this column should not be interpreted as obtaining individual financial planning or investment advice. For major financial decisions it is always wise to consult skilled professionals. While an effort has been made to be accurate, any statements of fact should be independently checked if important to the reader.

Disclosure: The author of this column holds the following ETFs mentioned in this article: VAB, VCN, XAW and XQB.